The effect of stochastic storage cost

By Tim Leung, Ph.D.

The fundamental principle in derivatives pricing is the absence of arbitrage opportunities. Standard no-arbitrage pricing theory asserts that spot and futures prices must converge at expiration.

Nevertheless, for years traders have observed significantly higher expiring futures prices for corn, wheat, and soybeans on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) compared to the spot price of the physical grains.

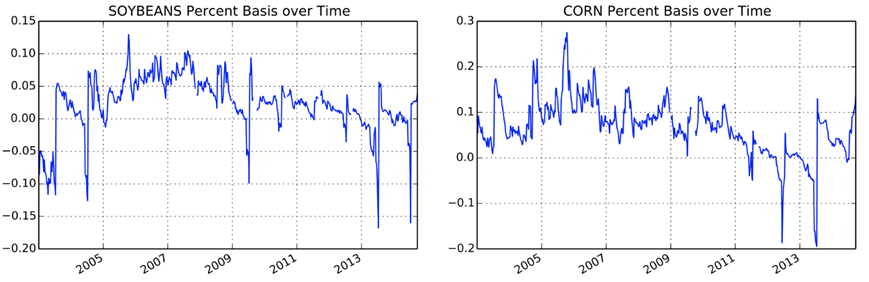

As shown in Figure 1, the differential between futures and spot prices, called the basis, can be positive or negative, but are more likely to be positive over a multi-year period. The basis reached its apex in 2006, where at the height of the phenomenon, CBOT corn futures had surpassed spot corn prices by almost 30%!

Fig. 1: Time series of basis (futures price — spot price) for soybeans (left) and corn (right) futures. During 2004–2009, the expiring futures price tends to be significantly higher than the spot price.

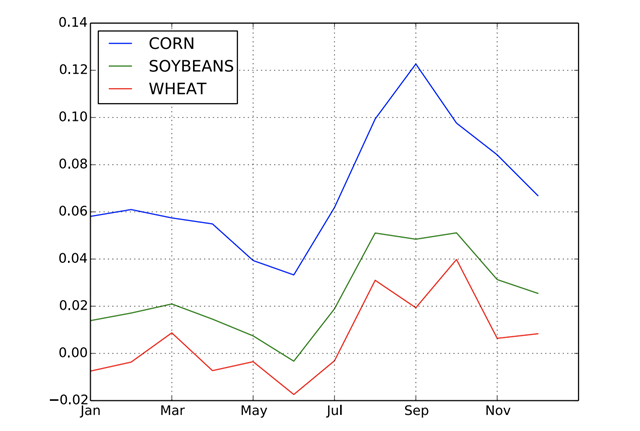

There’s also a clear seasonality in the basis. The average bases for corn, soybeans, and wheat is highest during the harvest months (August-October) as storage rates are high due to grain silo capacity constraint. For instance, the average basis for soybeans exceeds 12% in September. From February to June, the basis tends to be smaller since the storage costs are lower due to empty grain silos before the next harvest begins.

Seasonality of the average basis for corn, soybeans, and wheat during 2004– 2010.

Irwin et al. (2009) first coined the term “non-convergence” for this phenomenon of observed positive premium, which recurred persistently from 2004 onwards. According to their study, “performance has been consistently weakest in wheat, with futures prices at times exceeding delivery location cash prices by $1.00/bu, a level of disconnect between cash and futures not previously experienced in grain markets.”

Long-Side Options

However, a small difference between expiring futures and cash prices does not necessarily imply a market failure. Before expiration, futures and cash prices may differ due to the convenience yield, storage costs, or financing costs.

Upon expiration, if cash prices are lower/higher than futures prices, then arbitrageurs may profit from trading simultaneously in the spot and futures markets. If sufficient numbers of arbitrageurs engage in these trades, they will drive cash and futures prices to convergence at expiration.

In fact, the futures expiration date and delivery date may also differ. After the last trade date, the exchange contacts the longest outstanding long who is notified of his obligation to undertake delivery. Before the month’s end, the delivery instrument is then exchanged at the settlement price between long and short parties. Therefore, since the delivery process does not occur immediately after the last trade date, cash and futures prices might still differ.

Since the short party may choose the location and time to deliver, one may argue that futures price should be biased below the spot price on the last trade date. However, this would yield the opposite of the empirical observations in the grain markets. In fact, the positive basis in the CBOT grain markets between 2004–2009 were too large to have been caused by the small inefficiencies of the delivery process.

This motivates us to investigate the factors that drive the non-convergence phenomenon.

In order to explain the positive premium, one must turn to embedded long-side options in the futures.

Long-side options in futures markets depend totally on the idiosyncrasies of each commodity’s exchange traded structure. The appropriate model for a commodity varies highly depending on storability, instantaneous utility, and alternatives.

At expiration, a CBOT agricultural futures contract does not deliver the physical grains but an artificial instrument called the shipping certificate that entitles its holder to demand loading of the grains from a warehouse at any time. Before exercising the option to load, the holder must pay a fixed storage fee to the storage company, as stipulated in the certificate.

Since the storage capacity of grain elevators is limited and expensive, the number of grain elevators is fixed to a minimum necessary to efficiently carry out transfers of grain from one transport system to another. Thus, like a fractional-reserve banking system, shipping certificates alleviate the congestion of grain elevators by only keeping enough grain on hand to satisfy instant withdrawal demand.

A closer look via stochastic modeling.

Stochastic Storage Cost Model for Grains Futures

In our paper, we present a storage differential hypothesis: when the certificate storage rate is sufficiently low, investors will pay a premium for the certificate over the spot grain in order to save on storage cost over time, resulting in non-convergence of futures and spot prices.

When the storage cost of the certificate is set lower than the true storage cost paid by the regular firm, the regular firm will cease to issue the unprofitable shipping certificates. Since shipping certificates can only be issued by a set number of regular firms with limited inventories, the market cannot issue certificates with lower fixed storage rates to keep the market flowing. Instead, since the supply of certificates remains fixed, the value of existing shipping certificates will be bid up in the secondary market, resulting in a premium over the spot price.

On the other hand, during periods where the certificate storage rate is set much higher than the market storage rate, the certificate should not command any premium over the spot because agents would exercise and store at the lower market rate. Therefore, large quantities of certificates remaining unredeemed under the storage differential hypothesis becomes a strong predictor of non-convergence. In fact, under mounting evidence that storage differentials were responsible for non-convergence, the CBOT raised the certificate storage rate for wheat, after which non-convergence decreased significantly. This observation is consistent with our findings in this paper

We propose two new models that incorporate the stochasticity of the market storage rate and capture the storage option of the shipping certificate by solving two optimal timing problems, namely, to exercise the shipping certificate and subsequently liquidate the physical grain.

By examining the divergence between expiring futures prices and corresponding spot prices, we derive the timing option generated by the differential between the market storage rate and the constant storage rate stipulated in the shipping certificate, which explains the non-convergence phenomenon in agricultural commodity markets.

The core mathematical problem within our stochastic storage cost models is an optimal double stopping problem. To this end, we adapt to our problem the results developed by Leung et al. (2015) that study the optimal entry and exit timing strategies when the underlying is a mean-reverting process.

Among our results, we provide explicit prices for the shipping certificate, futures prices, and the basis size under a two continuous-time no-arbitrage pricing models with stochastic storage rates.

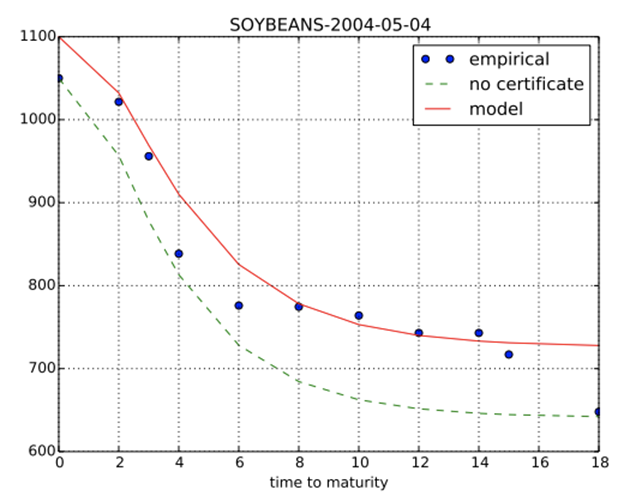

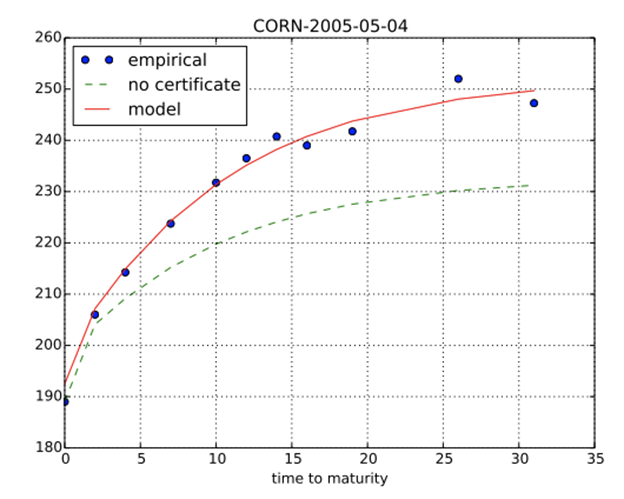

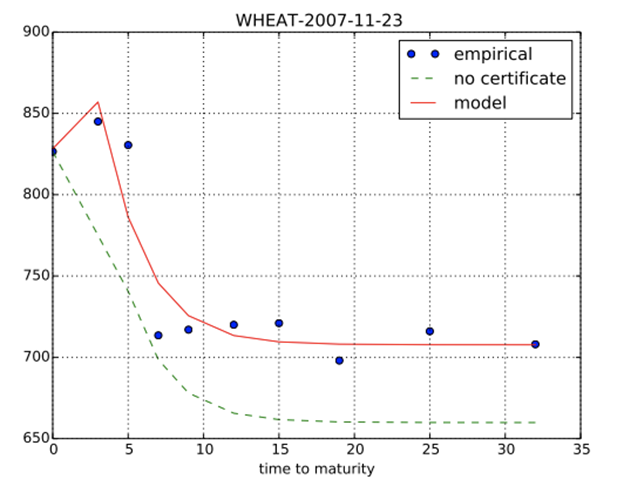

We also fit our model prices to market data and extract the numerical value of the embedded timing option.

Calibrated futures curves with and without the shipping certificate. Clearly shipping certificate carries a positive value that’s embedded in the futures contract.

References

K. Guo and T. Leung (2017). Understanding the non-convergence of agricultural futures via stochastic storage costs and timing options, Journal of Commodity Markets, Vol 6, June 2017, Pages 32–49 [pdf;link]

Irwin, S. H., Garcia, P., Good, D., and Kunda, E. (2009). Poor convergence performance of CBOT corn, soybean and wheat futures contracts: Causes and solutions. Marketing and Outlook Research Report.

Disclaimer

This article represents the opinions and view of the author(s) and not, necessarily, of Qdeck. The content of this article is provided solely for informational purposes and general education, and in no way should be considered investment advice.

This communication is provided for informational purposes and should not be construed as a recommendation or solicitation or offer to buy or sell futures contracts, securities or related financial instruments, nor as an official confirmation of performance. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Investment in any program is speculative and involves significant risks, including risks of loss. There can be no assurance that the programs will be able to realize their objectives.